For the October 16, 2009, issue of Playboy, Marge Simpson was the cover girl as a way to commemorate The Simpsons’ 20th anniversary. While naked, Margie is sitting behind a chair in the shape of the iconic bunny symbol with one leg crossed over the other and her shoulders raised to her earlobes in a casual yet timid pose. In an interview with the Associated Press, Jimmy Jellinek, chief content officer of Playboy, said, “She looks beautiful. She is a stunning example of the cartoon form. Marilyn Monroe. Madonna. Marge. It’s a fun continuity.”

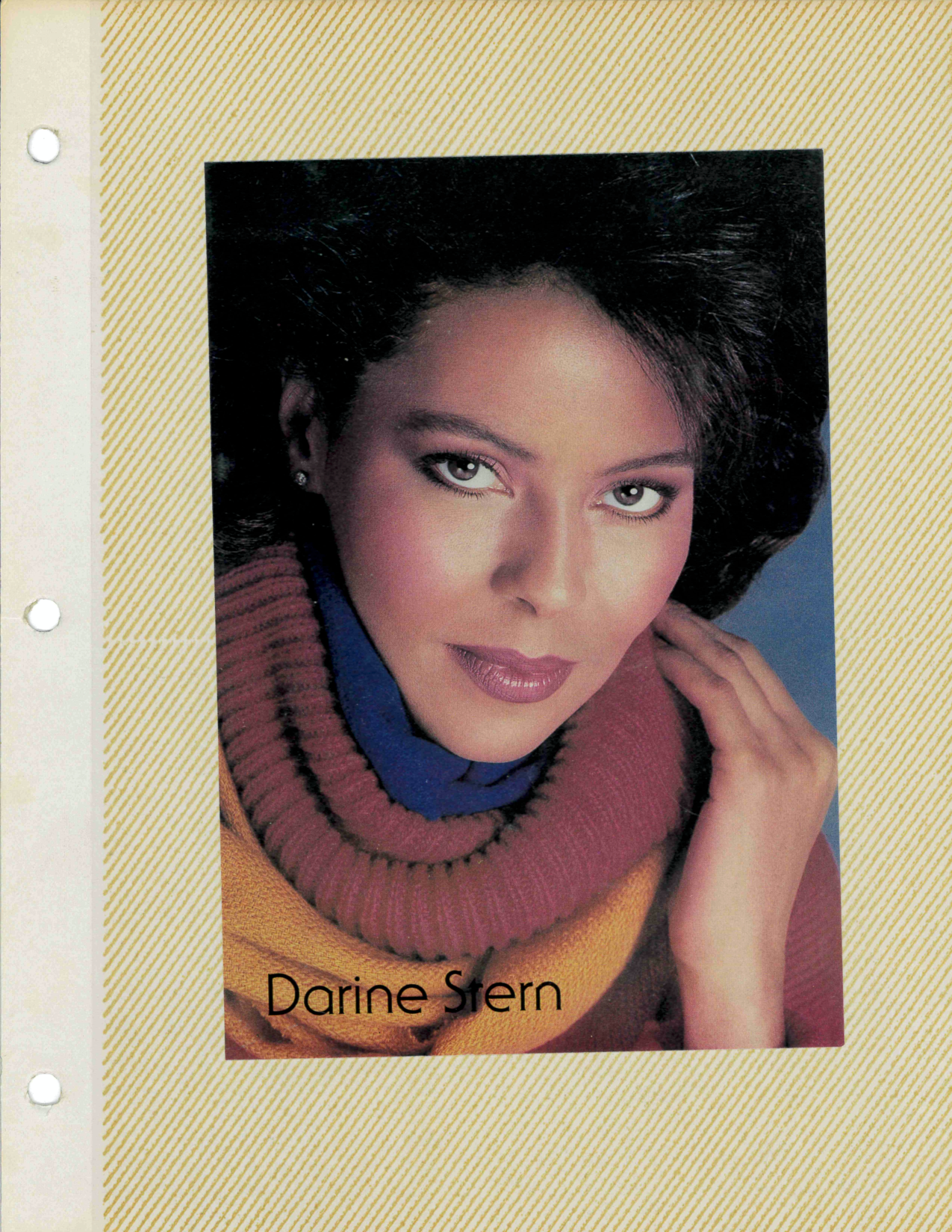

The cover choice was an effort to appeal to younger readers after the magazine suffered a sales decline, but what had gotten lost in the publicity rollout is the lack of homage to another woman from which the entire pose and style originated. The Hollywood Reporter mentioned a “black woman” who appeared on the 1971 cover in the exact pose but does not acknowledge her name. Many other competitive outlets leave out this woman entirely. Her name was Darine Stern, the first solo Black cover girl for Playboy, and her story offers a glimpse into the opportunities or lack thereof for Black models during the ’70s and ’80s, Black history of Chicago’s South and West Sides, and the media and publishing worlds.

Darine Stern was born November 16, 1947, in Chicago, Illinois. Her family was a part of the Great Migration, a pivotal moment in American history in which millions of African Americans fled the south for the north for better employment opportunities and to escape racial terrorism. It was actually the Chicago Defender who made the siren call to Black Americans in 1916 about southerners who made it in the big cities. They posted organizations where newcomers could turn to for help, and offered advice for how said newcomers could acclimate themselves to their metropolitan surroundings. Between 1916 to 1919, Chicago alone received approximately 50,000 to 75,000 Black southerners. But Chicago wasn’t an oasis by a long shot. Residential segregation was rampant. As more Blacks moved in, Whites moved further westward within the city limits or out in the suburbs accessible from the newly formed highways. A huge concentration of the city’s Black population was in an area called the “Black Belt” which was “formed on the south side between railroad tracks.”

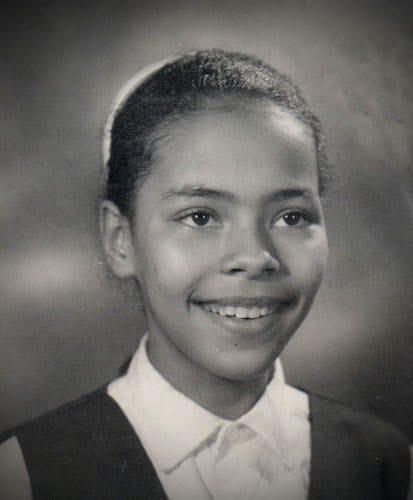

It is here on the South Side where Darine and her nine other siblings grew up. As a child, Darine was very family oriented, often clinging toward her older sister, Sheila for guidance: “Darine just wanted to be with me and my friends. Sometimes I wanted that and sometimes I wanted her to get her own friends.” Their mother was a hardworking woman who left a job as a credit officer for department stores due to discrimination and began to work as a truant officer for the Chicago public school system. She went through a series of marriages and oftentimes parts of the family would live in different places but throughout it all, Darine treasured the bonds she had with her siblings.

When Darine reached adolescence, she moved over to the West Side of Chicago where she attended Marshall Metropolitan High School. It was at Marshall that Darine’s beauty began to fascinate those around her. One of her other siblings, David, elaborated on how her looks benefited those in her orbit: “I had brothers who are very light skinned and they used to get their asses beat daily. But when they (the bullies) found out that Darine was their (brothers’) sister, they tried to be their long lost buddies.” Because of her looks, Darine was known around school, even being crowned prom queen at junior prom. But she never capitalized on her looks. She sought to become an educator and upon graduation, she left her family home and started to matriculate at Chicago State University.

Around the time Darine set out on her own, Playboy had reached its zenith. Starting in 1953 by a then 27-year-old Hugh Hefner, who was a former sociology student at Northwestern University, from the 1960s to the end of the 1970s, Playboy skyrocketed in annual sales from $4 million to $175 million. It was February 29, 1960, when Hefner started the Playboy Club on Walton Street in the Gold Coast section of Chicago. Two factors contributed to this establishment: Playboy was the leading men’s publication in the country and these male readers wanted to be a part of social gatherings that affirmed their standing as suave, stylish bachelors with a lot of cash to burn. Members, or keyholders, would be served cocktails by Playboy Bunnies (although there was a strict “look but don’t touch” policy).

Though mainstream magazines of that particular era were dominated with White faces, Playboy, in particular, was subversive not only for its exposure of the female form, but also for its politics.

Those who were employed as Bunnies had strict guidelines such as not dating customers, not giving out their phone numbers, and not allowing boyfriends or spouses within two blocks of the club. Darine began working at the Playboy Club in the late ’60s and had her admirers, including Bill Cosby. “He loved my sister,” brother David recounts. “He was crazy about Darine, He’d follow her around even. She liked him as far as his abilities and everything but she had no romantic feelings about him. From what she told me, he was respectful, kind, and there were never any problems.” Also at the Playboy Club is where she would meet her soon-to-be-husband, David Ray.

David Ray was a respected dentist with an equally impressive pedigree. His father was a geneticist and Howard University professor who once worked alongside Watson and Crick, discoverers of the human genome. His mother was also an educator as well as a nutritionist. Darine’s mother could not have been more thrilled. According to Sheila, “I think what my mother thought was once she does the modeling, she would still be married as a fallback. You need a fallback position. Mom wanted that security for her.” They married in 1970 and honeymooned in Jamaica.

Becoming a dentist’s wife was an enviable position, especially for a Black woman of the mid-20th century. And for a while, Darine acclimated herself to that role, aligning herself with a social set of two other couples and calling themselves “six-pack” while playing stepmother to David’s six-year-old son, David Jr. Whenever Darine could be convinced to go out onto the water (she couldn’t swim), David would take her sailboating or they’d watch television in the living room together as a family. Darine worked a series of other jobs in advertising, hostessing, and bank telling but it was the latter that changed the course of her life forever.

One day, a man came into the bank where Darine worked as a teller, complimented her looks, and asked if he could take her picture. She agreed and that man, who just so happened to be a photographer, brought those photos to the attention of the Playboy editorial team. Though mainstream magazines of that particular era were dominated with White faces, Playboy, in particular, was subversive not only for its exposure of the female form, but also for its politics. Hugh Hefner himself dove headfirst into civil rights activism, donating to the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, publishing Alex Haley long before his Roots fame, interviewing Miles Davis, and giving $25,000 as a reward to anyone who could find the bodies of slain Mississippi civil rights workers. In Jesse Jackson’s own words, “He was a change agent and a risk taker for racial equality and justice… Hef reached across the color line of fear and indifference.” Arguably these beliefs both personally and professionally are what opened a path of opportunity for Darine as a model.

Years before American Vogue, ELLE, and Harper’s Bazaar had a Black woman grace their cover, Playboy became a maverick. In fact, in 2005, the American Society of Magazine Editors listed this feat as one of the 40 most important magazine covers of the past 40 years.

Darine was proud of being a cover girl and her family was relieved that she wasn’t a centerfold where she most likely would have been fully nude without any shielding. She was mindful of her family and did not want to disappoint their expectations of her. Before Darine, Playboy had already featured two other Black models — March 1965’s Jennifer Jackson and October 1969’s Jean Bell — but neither had been a solo cover star. Two other White women were shot as outtakes for the October 1971 cover before Darine was chosen. For the cover, she wore an afro wig and the seat behind which Darine posed was designed right on the set. While other magazines were struggling with how to properly light and photograph darker skin, her image was taken behind a black background to contrast both her skin color and afro. She even lied to her mother that her naked body was airbrushed and that she was wearing a swimsuit in order to avoid scrutiny.

The cover was a runaway hit of an estimated 6 million copies in print. Years before American Vogue, ELLE, and Harper’s Bazaar had a Black woman grace their cover, Playboy became a maverick. In fact, in 2005, the American Society of Magazine Editors listed this feat as one of the 40 most important magazine covers of the past 40 years.

Almost immediately, Darine’s modeling career took off and her ambition soared. She began traveling between Chicago and New York, represented by Shirley Hamilton, Ford, Ellen Harth, and Nina Blanchard agencies. She graced other covers, such as Essence and the Chicago Sun-Times, and did print work for companies such as Virginia Slims and Ultra Sheen. But she would soon face challenges in both her professional and personal lives. The more demanding her work schedule became, the more her marriage to Ray suffered. Where Ray was consistent by working at a clinic during the day and then at a private clinic till late in the evening, Darine’s life required more versatility at a quicker pace than her former life as a dentist’s wife would allow.

Eventually, the couple agreed to part and divorce as Darine spent more time in New York and also some runway gigs in Europe. She poured herself deeper into the fashion industry but many doors were closed for one person in particular: Beverly Johnson. According to her former stepson David, “I remember her always feeling a bit of competition with Beverly Johnson but not out of spite. She was the first Black model to break through the old guard. She would have conversations with my dad about how Beverly Johnson would get certain jobs and she was trying to get the same jobs.”

“…in a business that offers such limited opportunities to Black women regardless of ‘the look,’ to be expected to fit a mold that was not you or to have to compete for a booking against a person who is known for what you are trying to effect in a casting puts you at a disadvantage in some respect.”

The 1970s were the heyday for Black models breaking into the mainstream fashion industry, a period that was precipitated by Naomi Sims becoming the first Black model to grace the cover of Ladies Home Journal in 1968. There were other predecessors, such as Donyale Luna, who was the first African American model to be on the cover of British Vogue, and Dorothea Towles Church, who modeled for houses such as Schiaparelli, Dior, and Balmain. However, most Black models looked to Europe to have any kind of considerable success. Eric Darnell Pritchard, associate professor in the English department at the University of Buffalo, said, “In the case of Johnson, when she became the first Black model to appear on the cover of Vogue Magazine in 1974, that of course meant that her look was one that some other magazines, beauty companies, and other commercial advertisers would seek. As such, modeling agents undoubtedly would want at least one or more clients who had the Beverly Johnson look.”

There were other “looks” — those of Bethann Hardison, Iman, Mounia, Alva Chinn, and Pat Cleveland. However, in the words of Pritchard, “…in a business that offers such limited opportunities to Black women regardless of ‘the look,’ to be expected to fit a mold that was not you or to have to compete for a booking against a person who is known for what you are trying to effect in a casting puts you at a disadvantage in some respect.” In Darine’s case, as she would relay to her family during many exasperated conversations, she was either “too Black” or “not Black enough.”

But shouldn’t Stern’s groundbreaking cover mean an abundance of offers? Not quite. She quickly learned that the New York world was much more cutthroat and elitist than the streets of Chicago. According to Marcellas Reynolds, former model, fashion stylist, and author of Supreme Models: Iconic Black Women Who Revolutionized Fashion, “There are models who do fashion editorials and runway, then there are catalog models, then commercial models. Those worlds seldom mix… Appearing in the pages of Playboy, which for many of its centerfolds was an entree into acting, definitely excluded someone from legitimate work as a fashion model. Add to that the role race played in fashion, further limiting the amount of available work, and there was no place for Darine.”

Frustrated by the lack of modeling opportunities, Darine moved to Los Angeles for newer pastures but was not fond of the city’s scene or the Hollywood industry in its entirety. She was a photographer’s model and she wasn’t inspired by film or music to make a transition there. She returned to Chicago and worked as a fashion director at Burrell Advertising Agency and also provided image consultation and costume design for the likes of Lena Horne, Aretha Franklin, and Michael Jordan. In addition, she created Darine Stern Agency to foster the careers of emerging models and provided talent for clients such as Sears, Canadian Mist, Kellogg’s, and Ford Motor Company, though it shut down within a few short years.

In the late ’80s, Darine moved to Martha’s Vineyard where she assisted choreographer Marla Blakey on a For Colored Girls production and acted in a soap opera pilot centering the lives of those who live in Oak Bluffs, a historic, African American community within Martha’s Vineyard, that never aired. Throughout her multilayered career, Darine was worried about her looks. “Beauty,” as her sister Sheila puts it, “is a double-edged sword. It can cut through anything but it can cut you.”

For Darine, a woman now in her forties, would ask her sister Sheila how she looked for her age and entertained the thought of plastic surgery. Unbeknownst to Darine, she would not be going to a doctor to salvage her looks but rather her life, for she was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 43. Speaking with Blakey about Darine’s cancer diagnosis, she emphatically tells me, “She did everything she could to get better — holistics, eating right, exercising. She did everything.” She befriended Cheryl Stark and Margery Meltzer through a local cancer support group and they became inseparable. “She was so young,” Meltzer says. “Even when she became ill, her spark always showed through. She was a loving, gentle soul with a quick wit.” She tried to get stem cell treatment but she wasn’t responding well enough to the preliminary cycles to qualify. When the cancer was metastasizing, one of her friends since her time at the Playboy Club used her money to put Darine on a plane back to Chicago.

There at a hospice, relatives and other loved ones would move in and out of the room. Most times, Darine wouldn’t speak. That is until Ray came to visit. Her brother David recounts, “Obviously she was carrying some kind of torch for him because she revived when he walked in the room.” In Darine’s last call to Meltzer, she had a vision: “…she told me she’d had a dream the night before in which I was having a ‘party’ to celebrate her life with lots of people. I assured her that I would do that and I did.”

On February 5, 1994, Darine Stern passed away. A memorial scholarship in her honor was created at Chicago State University where she once studied education before fully pursuing professional modeling. Her most famous image still belongs to Playboy. Since her passing, her sister Sheila has kept an archive of many of her sister’s headshots, editorial spreads, letters, and résumés as a way to keep Darine’s legacy alive. Though Darine is considerably lesser known than her contemporaries, her story demonstrates the constraints of what Black women could have been and the flowers they could have been given while they still were alive. It is a bittersweet reminder of where we’ve arrived and an admonition of what more needs to be done so that Black women will no longer be footnotes throughout turning points in our culture.