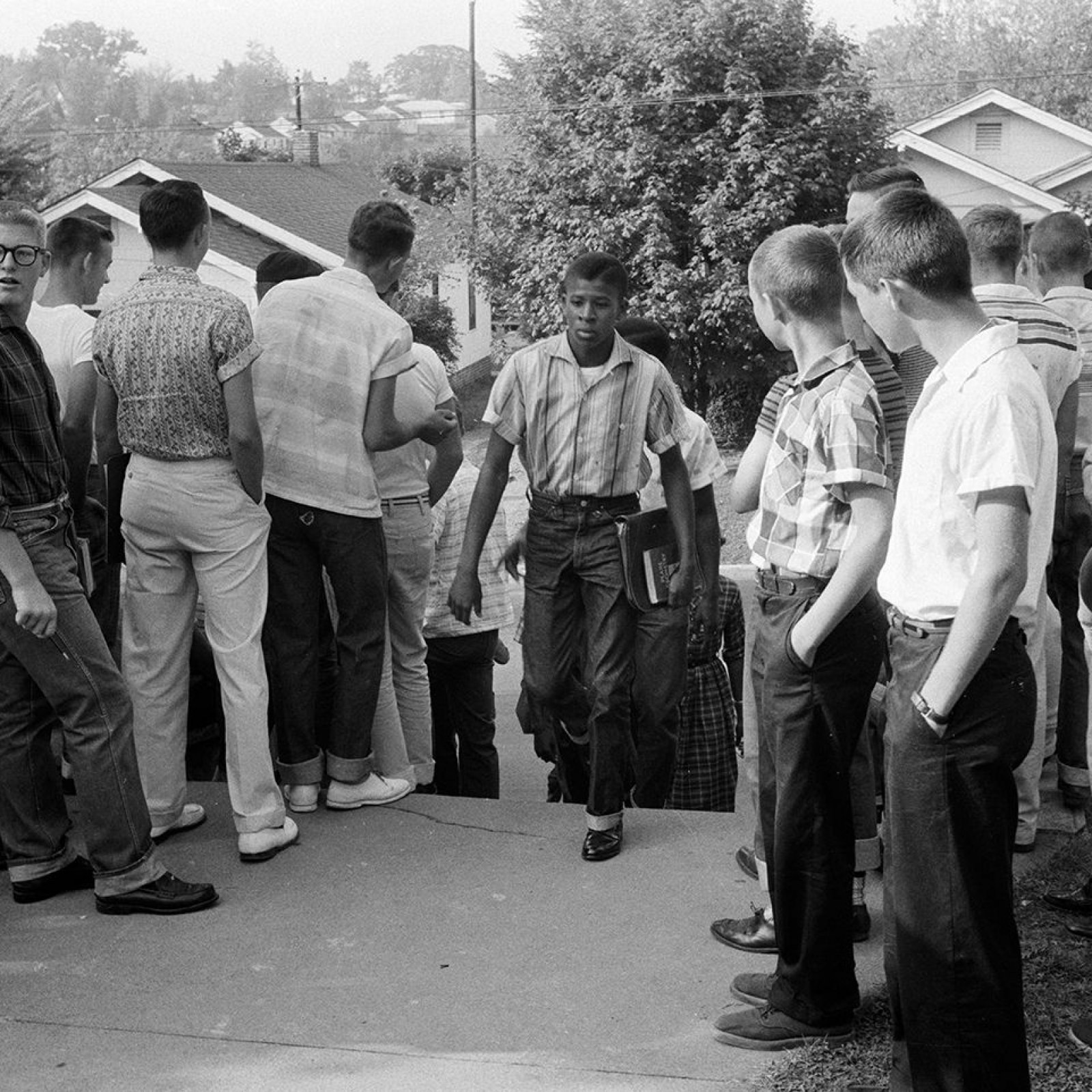

In the summer of 1955, administrators at the University of Texas at Austin had a problem: The U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision, handed down the previous year, required educational institutions to integrate their classrooms. But the regents overseeing the state university system’s flagship campus, the old alumni who formed the donor base, and the segregationist political forces that pulled the purse strings were all determined to find ways to keep African Americans from stepping foot on campus.

UT had no conspicuous blocking-the-schoolhouse-door moment. A series of documents in the UT archives, many of them marked confidential, suggests that administration officials took a subtler approach: They adopted a selective admissions policy based around standardized testing, which they knew would suppress the number of African American students they were forced to admit.

I came across these little-discussed records, all but lost to history, while researching my book about the football player Earl Campbell and desegregation. (Campbell played at Texas in the mid-1970s, not long after the head coach finally allowed African Americans on the varsity squad.) In recent years, the university has tried to reckon with its past: Confederate statues have been removed and a portrait of Heman Sweatt, the African American postal worker whose application to the university in the mid-’40s led to a Supreme Court decision that presaged Brown, now hangs in the atrium of the law school that sought to bar his entry.

Historically, however, the university went to great lengths to perpetuate white supremacy. Today, standardized testing is widely seen as an objective index of merit. In Texas, in the immediate post-Brown era, it seems to have been used as a bureaucratic cudgel to maintain Jim Crow.

Less than two weeks after the Brown ruling, in May 1954, H. Y. McCown, the university’s admissions dean, dashed off a note to the university president with a proposal to “keep Negroes out of most classes where there are a large number of girls.”

“If we want to exclude as many Negro undergraduates as possible,” McCown wrote, the university should require African American students seeking admission to undergraduate professional programs to first spend a year taking courses at Prairie View A&M or Texas Southern University, both black schools. Essentially ignoring the thrust of Brown, the regents adopted the proposal.

But the gap-year solution was only a temporary one. In June 1955, the four-person Committee on Selective Admissions, composed of senior faculty and high-ranking administrators, argued that if UT loosened the graduate-student application process, “the University would be in a position to plead that it is acting in good faith to bring an end to segregation, and it should have some bearing with the courts in any attempt to postpone the admission of Negro students at the undergraduate level.” The university had already been forced to integrate the graduate-student ranks after the 1950 Sweatt decision; the committee seems to have been suggesting that graduate-school admissions would act as a fig leaf for obstruction at the undergraduate level.

The committee went on to observe that if the 2,700-person freshman class was admitted according to state population proportions, 300 would be black. And it noted that white UT freshmen had significantly higher aptitude-test scores than incoming freshmen at three Texas black colleges. A standardized-test cutoff “point of 72 would eliminate about 10% of UT freshmen and about 74% of Negroes,” the committee stated in a footnote. “Assuming the distributions are representative, this cutting point would tend to result in a maximum of 70 Negroes in a class of 2,700.”

In a cover letter to the report, committee members included advice that further suggests they were at the very least mindful of, if not pleased by, the role standardized testing would play in the admission of black students: “We suggest that the President of the University in the near future ask the other state institutions to exchange ideas on this subject and if possible to collaborate in the program of testing. In these discussions, the admission of Negroes will naturally have a prominent place.”

There are, of course, many reasons a university might impose a testing regime. Until the mid-20th century, UT practiced an open-admissions policy—at least for nonblack applicants, as the scholars Thomas D. Russell and Dwonna Goldstone have explained. But a postwar boom in students, including returning GIs, raised doubts about how long such a policy could remain tenable. In The Big Test, Nicholas Lemann points out that many large universities in the 1950s adopted the SAT because they aspired to transform themselves into elite research institutions. But UT moved firmly in this direction only when administrators saw an anti-integrationist virtue to testing.

University officials, knowing further litigation was likely, and under some pressure from the young, more progressive student body and certain newspapers, tried to mask their segregationist impulses. “Make a virtue out of a necessity” one UT official jotted down at the time of the Supreme Court’s original integration order. (The note, which can be found on a scrap of paper in the UT chancellor’s records in the university archives, is unsigned.) Soon after the Committee on Selective Admissions delivered its report, L. D. Haskew, vice president for developmental services at UT, recommended that officials use the term guided admissions rather than selective admissions.

“I believe it is a good choice for public relations,” he wrote. The university “will point out to some of them difficulties they will have to surmount” and “will also reveal to some students that they should not enter the University of Texas. Another college may be better suited to their particular combination of abilities and needs.”

In July 1955, the regents issued a public statement that new admissions standards based on testing would be imposed in time for the 1956-1957 school year because UT was expecting “many more applications for admission on the undergraduate level than can be adequately accommodated.”

That August, UT President Logan Wilson gave a speech to the Rotary Club of Houston, assuring a group that included influential alumni that pending desegregation was “not prompted by missionary or reformist motives.” The notes for Wilson’s speech, housed in the UT archives, leave little doubt that the university knew exactly what it was doing: “Merely a realistic acceptance of inevitable to avoid legal hassles. Sensible compliance with Supreme Court decision. Do not anticipate any great numbers of N’s, but to avoid appearing to discriminate against unqualified have tied it in with a selective admissions policy for all students without ref. to racial origin, etc.”

I asked university officials about these documents and what they suggest about why UT adopted standardized testing.

“The historical record makes it clear that racism was a primary motivation in UT’s decision in the 1950s to begin testing applicants for admission,” said Gary Susswein, a UT Austin spokesman. “Other explanations were given at the time, as standardized testing took root nationally and many universities moved away from open admissions to become more selective. But the ugly desire to keep out African American students was a major driver of that policy.”

The officials said the wrongs of the past underline the benefits of creating an inclusive environment today.

“The university’s past history of discriminating against African Americans drives us to be leaders today in serving all qualified students,” Leonard Moore, vice president of diversity and community engagement at UT Austin, said in a statement. “After fighting integration at the Supreme Court in the 1950s, The University of Texas returned in the 2010s to successfully defend the educational benefits of diversity and the use of race and ethnicity as one factor in admissions.”

Moore was referring to the fraught story of affirmative action at UT. In 1996, a federal court struck down UT law school’s affirmative-action policy, in Hopwood v. Texas, for Cheryl Hopwood, one of four white students who sued the university alleging they had been discriminated against because the law school gave preferential treatment to people of color. The state adapted while preserving some form of affirmative action by guaranteeing admission to all state universities for students who graduated in the top 10 percent of their Texas high-school class. (The rule is now limited to the top 6 percent at UT Austin.) It’s a sideways form of affirmative action: By guaranteeing admission to students from all corners of the state, including from high schools that are chiefly black or Latino, the law has increased geographic and racial diversity in the admissions process.

Today, at least three-fourths of UT’s freshmen from Texas gain admission this way. Most other applicants receive a so-called holistic review that takes race and ethnicity into account along with grades, essays, leadership qualities, and numerous other factors, including standardized-test scores.

But this holistic review has recently come under attack as well. In May, the university was sued by a familiar adversary: Edward Blum, a 1973 alumnus of the university, who failed, as recently as 2016 in the Supreme Court, in challenging the university’s admissions policies. “It is our belief that the Texas Constitution unequivocally forbids UT-Austin from treating applicants differently because of their race and ethnicity,” Blum said in May. Blum and the plaintiffs he underwrites want Texas to be “color-blind,” to discount completely race and ethnicity and opt for purely “objective” admissions.

Perhaps, though, there is no such thing. Decades ago, administrators at UT calculated that standardized tests would tamp down the number of African Americans at UT. Now Blum and his plaintiffs, aiming for a so-called objective approach to admissions, appear to be carrying that torch. Standardized testing’s reputation as a purely objective measure remains complicated—and perhaps inevitably tainted—by this country’s legacy of racism.

by Asher Price