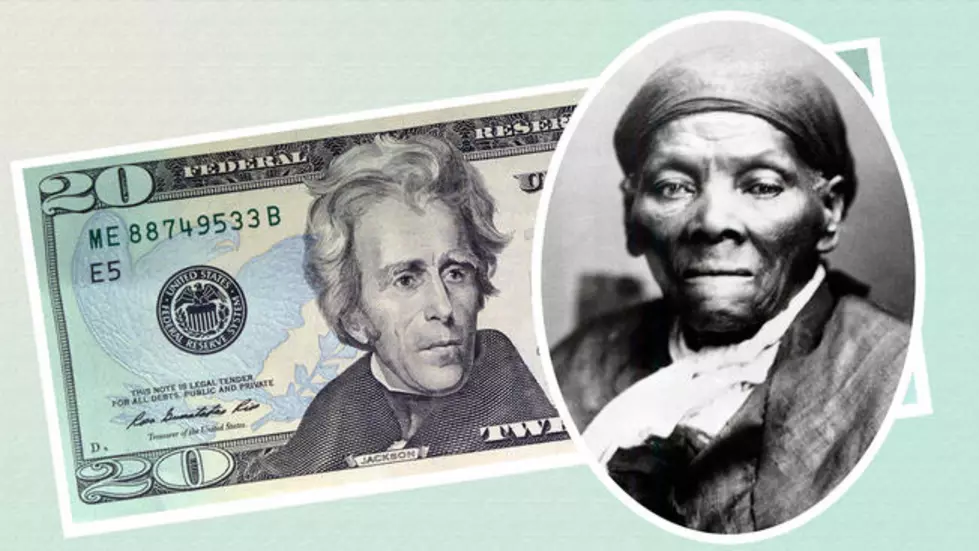

Extensive work was well underway on a new $20 bill bearing the image of Harriet Tubman when Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin announced last month that the design of the note would be delayed for technical reasons by six years and might not include the former slave and abolitionist.

Many Americans were deeply disappointed with the delay of the bill, which was to be the first to bear the face of an African-American. The change would push completion of the imagery past President Trump’s time in office, even if he wins a second term, stirring speculation that Mr. Trump had intervened to keep his favorite president, Andrew Jackson, a fellow populist, on the front of the note. But Mr. Mnuchin, testifying before Congress, said new security features under development made the 2020 design deadline set by the Obama administration impossible to meet, so he punted Tubman’s fate to a future Treasury secretary.

In fact, work on the new $20 note began before Mr. Trump took office, and the basic design already on paper most likely could have satisfied the goal of unveiling a note bearing Tubman’s likeness on next year’s centennial of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote.

An image of a new $20 bill, produced by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and obtained by The New York Times from a former Treasury Department official, depicts Tubman in a dark coat with a wide collar and a white scarf. That preliminary design was completed in late 2016.

A spokeswoman for the bureau, Lydia Washington, confirmed that preliminary designs of the new note were created as part of research that was done after Jacob J. Lew, President Barack Obama’s final Treasury secretary, proposed the idea of a Tubman bill.

The development of the note did not stop there. A current employee of the bureau, who asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the matter, personally viewed a metal engraving plate and a digital image of a Tubman $20 bill while it was being reviewed by engravers and Secret Service officials as recently as May 2018.

This person said that the design appeared to be far along in the process. Within the bureau, this person said, there was a sense of excitement and pride about the new $20 note. But the Treasury Department, which oversees the engraving bureau, decided that a new $20 bill would not be made public next year. Current and former department officials say Mr. Mnuchin chose the delay to avoid the possibility that Mr. Trump would cancel the plan outright and create even more controversy.

In an interview last week, Mr. Mnuchin denied that the reasons for the delay were anything but technical. “Let me assure you, this speculation that we’ve slowed down the process is just not the case,” Mr. Mnuchin said, speaking on the sidelines of the G-20 finance ministers meeting in Japan.

The Treasury secretary reiterated that security features drive the change of the currency and rejected the notion that political interference was at play. He declined to say if he believed his predecessor had tried to politicize the currency. “There is a group of experts that’s interagency, including the Secret Service and others and B.E.P., that are all career officials that are focused on this,” he said, referring to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. “They’re working as fast as they can.” Monica Crowley, a spokeswoman for Mr. Mnuchin, added that the release into circulation of the new $20 note remained on schedule with the bureau’s original timeline of 2030. She did not, however, say that the bill would feature Tubman.

“The scheduled release (printing) of the $20 bill is on a timetable consistent with the previous administration,” she said in a statement. But building the security features of a new note before designing its images struck some as curious. Larry E. Rolufs, a former director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, said that because the security features of a new note are embedded in the imagery, they normally would be created simultaneously.

“It can be done at the same time,” said Mr. Rolufs, who led the bureau from 1995 to 1997. “You want to work them together.” The process of developing American currency is painstaking, done by engravers who spend a decade training as apprentices. People familiar with the process say that engravers spend months working literally upside down and backward carving the portraits of historical figures into the steel plates that eventually help create cash.

Often, multiple engravers will attempt different versions of the portraits, usually based on paintings or photographs, and ultimately, the Treasury secretary chooses which one will appear on a note. Mr. Rolufs said that because of the complexity of creating new currency, circulating a new note design by next year was ambitious. He also acknowledged that making major changes to the money is an invitation for backlash. “For the secretary to change the design of the notes takes political courage,” he said. “The American people don’t like their currency messed with.”

As a presidential candidate, Mr. Trump called the decision to replace Jackson, who was a slave owner, with Tubman “pure political correctness.” An overhaul of the Treasury Department’s website after Mr. Trump took office removed any trace of the Obama administration’s plans to change the currency, signaling that the plan might be halted. Within Mr. Trump’s Treasury Department, some officials complained that Mr. Lew had politicized the currency with the plan and that the process of selecting Tubman, which included an online poll among other forms of feedback, was not rigorous or reflective of the country’s desires.

The uncertainty has renewed interest in the matter. This week, Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland, where Tubman was born, wrote a letter to Mr. Mnuchin urging him to find a way to speed up the process. “I hope that you’ll reconsider your decision and instead join our efforts to promptly memorialize Tubman’s life and many achievements,” wrote Mr. Hogan, a Republican. And last week, a group of House Democrats demanded that the Treasury secretary provide specific information about the security concerns that were impeding the currency redesign. At the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which offers tours and an exhibit on the history of the currency, some visitors said they preferred tradition, while others were seeking change.

“For me, it’s not important enough to spend the money to change it,” said Jeff Dunyon, who was visiting Washington from Utah this week. “There are other ways to honor her.” Others believed that adding Tubman to the front of the $20 bill and moving Jackson to the back was an important symbolic move, and, for them, the possibility that it might never happen has been painful. Charnay Gima, a tourist from Hawaii, had just finished a tour when she pulled aside a guide to ask a question that was bothering her. She wanted to know what became of the plan to make Tubman the face of the $20 bill.

To Ms. Gima’s dismay, there was no sign of Tubman in any of the bureau’s exhibits. The plan was scrapped, she was told, for political reasons. “It’s kind of sad,” said Ms. Gima, who is black. “I was really looking forward to it because it was finally someone of color on the bill who paved the way for other people.”

Mikayla Bouchard