On the fifth Sunday of Lent, a week into the governor’s order limiting gatherings of more than 50 people in Louisiana, Pastor Tony Spell of Life Tabernacle Church in Baton Rouge used the church’s 27 buses to shuttle people to a tent revival service. This week, Spell defended holding services during the pandemic in a video that was published on TMZ. “True Christians do not mind dying,” he said. “They fear living in fear.”

In Ohio, Solid Rock Church defied the statewide stay-at-home order and continued holding services. On its website, Solid Rock explains it is taking the temperature of the staff each day, avoiding Communion, and encouraging worshippers to stand six feet apart.

Ohio, which is succeeding in flattening the curve through aggressive stay-at-home measures, exempts church gatherings from its stay-at-home order, although Governor Mike DeWine has called continuing to gather in large groups “not a Christian thing to do.” After Tampa Bay River megachurch pastor Rodney Howard-Browne was arrested for holding services in defiance of his county’s stay-at-home order, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis issued an overriding order that does not bar churches from holding services.

This Holy Week, days before Easter, Kansas’s state legislature revoked the governor’s order limiting religious services to 10 people. Other states that have made exemptions or recommendations for parishioners and places of worship in their stay-at-home directives include Delaware, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, and West Virginia.

Following public health guidance, the vast majority of the nation’s religious bodies have moved services online, or like Ohio’s Mt. Zion Baptist Church, created alternatives, such as a drive-in option with driver-side donation offerings and car honks for “amens.” The estimated 7% of Protestant churches that were still holding in-person meetings by the end of March have been publicly met with the sort of scorn that now gets directed to spring breakers or other social-distance flouters. Even staunch religious liberty advocates have voiced concerns that these outlier pastors putting lives in danger to grandstand will undermine future religious liberty arguments. They make it easy to paint Christians as caring more about their own gatherings than saving people’s lives.

But holding services during the pandemic, especially on Easter Sunday, is not just about religious freedom — it’s also about the money.

Lutheran Pastor Angela Denker, author of Red State Christians, found that from her own, admittedly anecdotal experience at two large churches and two small ones, large churches were financially dependent on offerings at Christmas Eve and Easter, when less frequent visitors were apt to come for the big show. (At smaller churches, the holiday crowd tracks closer to average Sundays, she says.) Her church in Las Vegas, for instance, ran in the red all year and made up for it with Christmas Eve and Easter.

For many churches, particularly large ones, Easter is the day with the highest attendance annually, and parishioners may be willing to give even more at Easter, since they haven’t just blown sizable amounts of their expendable income on Christmas gifts.

The way time has sloshed and stretched during this pandemic, it may feel like a lifetime ago that President Donald Trump hoped to have churches packed and the country “opened up and just raring to go by Easter.” That date was significant, not just for Trump’s evangelical base, and because Trump reportedly had just watched a pastor preach to a megachurch’s empty seats, but also because Easter is a huge day for donations for most churches, particularly megachurches.

Even beyond the biggest donation days, the sanitized concept of material “abundance” can be used to motivate greater giving. The idea that God will give back to those who share their own money is embedded in evangelical church culture throughout the country, thanks to prosperity gospel teachings popularized by best-selling celebrity pastors like Paula White and Kenneth Copeland, and Joel Osteen, whose net worth is $50 million.

Particularly in megachurches imbued with prosperity teachings, the faithful quid pro quo of weekly donations in exchange for God’s bounty keeps massive facilities running and builds the cachet of their pastors.

During our interview, Denker read me a common prosperity gospel trope from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible: “I have come that they might have life and have it abundantly” (John 10:10). It is indeed a biblical idea, she says, that Jesus came to give abundant life, not just life after death — that prayer and worship enriches one’s life on earth. “What the prosperity gospel does is sort of twist it and makes the Bible’s view of prosperity, which is a life that is rich with love and relationship and giving and forgiveness and kind of conflates that with a life that is rich with money and wealth and worldly power,” says Denker. Instead of promises of loving relationships through giving to others, giving — donations to one’s church and its ministries — comes with the promise of material goods, a big house, paycheck, car. It’s a compelling notion right now especially, when so many people are going without.

Yes, Christianity can be understood as a faith built around Jesus’s death and resurrection, which is celebrated on Easter Sunday. It’s also the day that balances the books for some churches and builds wealth for a few.

Holding services now, during the biggest donation day of the year and despite public health warnings, smacks of the worst sort of manipulation. Denker is appalled by stories of pastors bussing in people who probably lack other modes of transportation, and who might not have a lot of means: “This church knows that if they do not bus these people in, these people may not have internet access to give online.” Denker holds no grudge with believers craving the comfort of worship. “I’m mad at the pastors who are called to hold themselves to a higher standard to not put people’s lives at risk and not test God.”

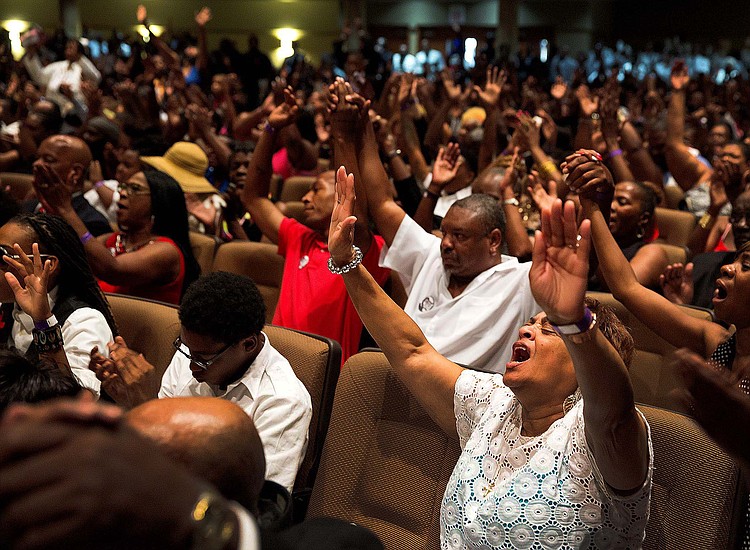

In the early days of shutdown orders, some Black churches were initially hesitant to close their doors, notes writer and theologian Candice Marie Benbow in an article for Zora. Some eventually started streaming but called in their choirs and production teams. Music is often an essential part of African American worship after all. “Religious tradition from the spirituals to contemporary gospel music to hip-hop… have carried us, have carried Black people through,” Benbow told me over the phone. But now, with the need to socially distance, it’s dangerous for choirs to get together in a confined space for an hour or 45 minutes, then go back home.

Some pastors weren’t accustomed to preaching without the choral response, without the amen corner. On the one hand, says Benbow, there’s a very real inability for some pastors to “envision church outside of what they have always done.” They don’t really know how “to maneuver and preach in a completely different context.” But with the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus on African American communities, pastors are having to adapt in a way that “honors the data that we’re getting.”

Even where prosperity theology exists in Black churches, where there’s a desire to stake a claim in the American dream, notes Benbow, the church’s own ministries often betray the fact that financial prosperity is not a reality for many in the congregation. Many of these congregations also have prison ministries, due to structural racism that leads to higher incarceration rates. These ministries feed an already financially vulnerable community — not as outreach to a separate, outside group, but because the congregation itself is food insecure.

To many already unstable lives, the coronavirus pandemic has added a month or more at home with kids whose schools are closed, adults laid off, and families needing groceries. Ministries to share food are crucial to the actual survival of the church.

The average pastor, says Benbow, is asking people to “continue financially investing in their congregations because they know that now more than ever, people are going to be pulling on their congregation.”

When a community is in crisis, there’s an urge to come together. On this upcoming holy day, people may feel the need to be with those who lift them from fear, who grieve with them. Some are looking for the promise of easier days. They hope for health, for money to cover the bills.

For Benbow, the church’s challenge isn’t hinged on this Sunday. It’s about what happens after Easter, what the church can learn from this time of forced quiet self-assessment. Because the church — whether rich, poor, mega- or community-size — is being changed and reshaped by this moment.