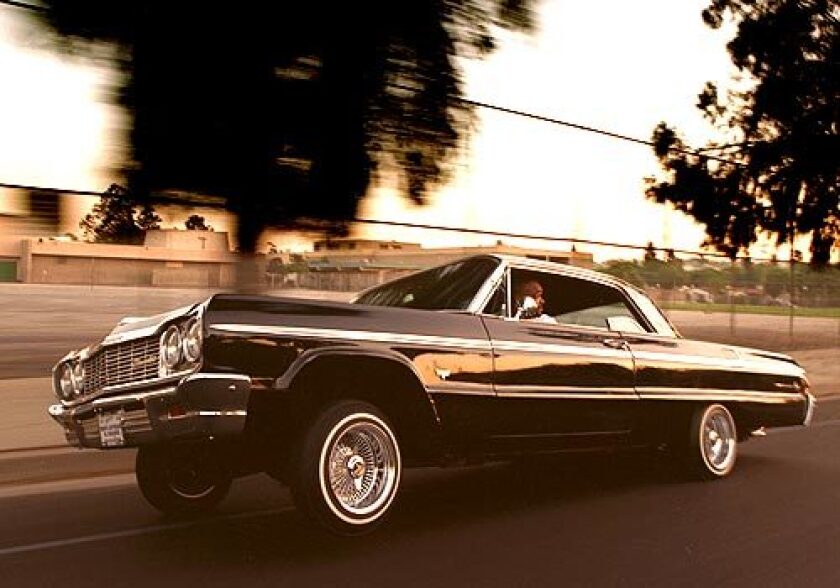

Jerry Navarro didn’t care about having a phone as a boy. He wanted a car. But what he really, really wanted was a lowrider: a white, 1958 hardtop Chevrolet Impala with a red interior.

So he started reading Lowrider magazine around 1985 in his hometown of East Los Angeles to indulge his fantasies of car ownership. Later, when he began working in the auto industry, the magazine became a rich and vital source of information about the car world.

“You wanted to see what was the hottest car, who was selling what, what tires were the best, and who was doing good interior. ... Back then there weren’t [smart]phones so you had to get information from magazines,” said the 45-year-old technician from Chuy’s Auto Electric Shop in East L.A.

Those days will soon be over, though. Lowrider, an icon of Chicano culture for more than 40 years that offered a mix of cultural and political content alongside photographs of unique vintage cars, will cease to print.

The magazine is one of 19 titles that TEN: The Enthusiast Network will shutter by year’s end, the media company announced Dec. 6.

“Simply put, we need to be where our audience is,” wrote MotorTrend Group President and General Manager Alex Wellen in a memo obtained by Folio. “Tens of millions of fans visit MotorTrend’s digital properties every month, with the vast majority of our consumption on mobile, and three out of every four of our visitors favoring digital content over print.”

According to the memo, MotorTrend Group “will continue to offer our audiences and advertisers digital coverage for these discontinued print titles online.”

A representative for MotorTrend Group would not comment further but issued a statement to The Times.

“We remain committed to providing our fans and advertisers quality automotive storytelling and journalism across all of our content platforms and we are doubling down on our best-in-class digital product experiences, while maintaining our support of the three most popular, profitable and strategic brands across digital and print — MotorTrend, Hot Rod and Four Wheeler,” the statement read.

MotorTrend Group, which manages the digital and video brands online, is a company independent of TEN Publishing and was not involved in the decision to shutter the print titles.

TEN Publishing, MotorTrend Group and Lowrider staff would not comment further on the closure.

For decades, Lowrider played a critical role in forming the culture and image of lowriding, its lifestyle and aesthetics. Particularly popular among Mexican Americans, the magazine was as much a statement about Chicano identity as it was about the long, ground-hugging vintage cars.

Lowrider was first published in 1977, founded by San Jose State students Larry Gonzalez, David Nuñez and Sonny Madrid (Nuñez died in 2011, Madrid in 2015). With a shared mission to feature the Chicano lowrider community, the trio pitched in a few thousand dollars each to get the magazine off the ground and distributed its first copies — roughly 1,000 — in January that year.

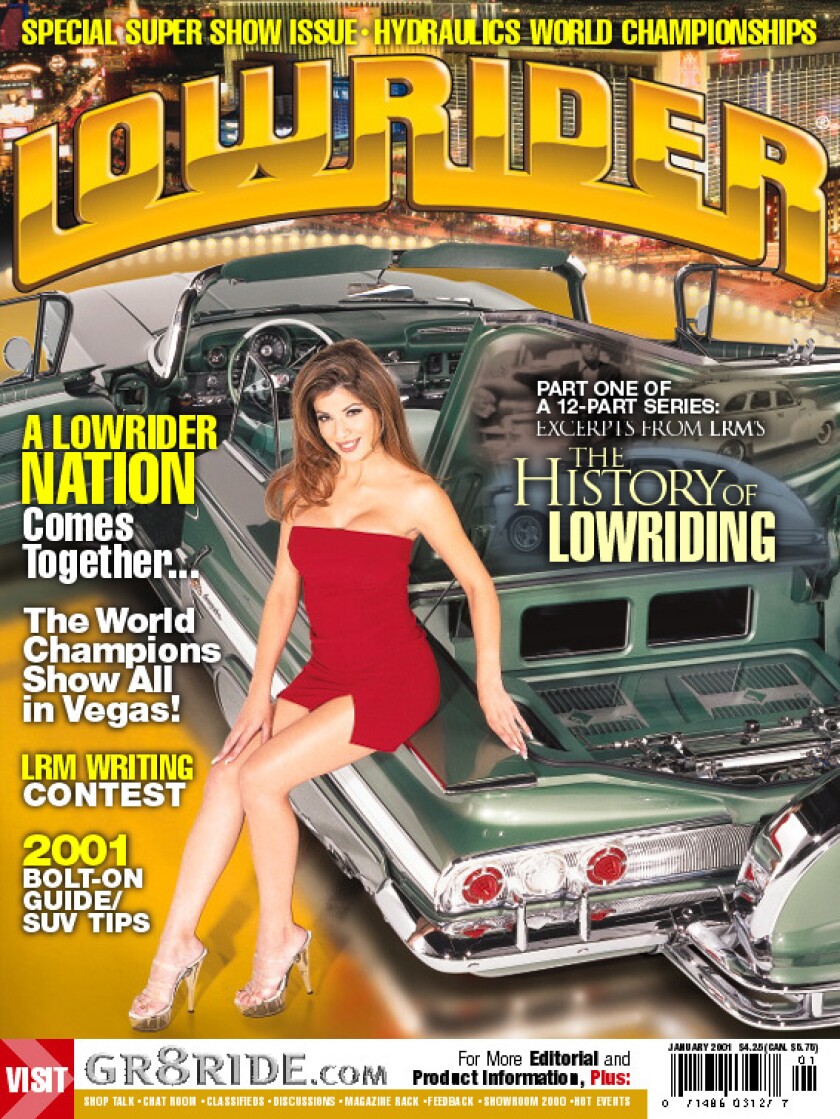

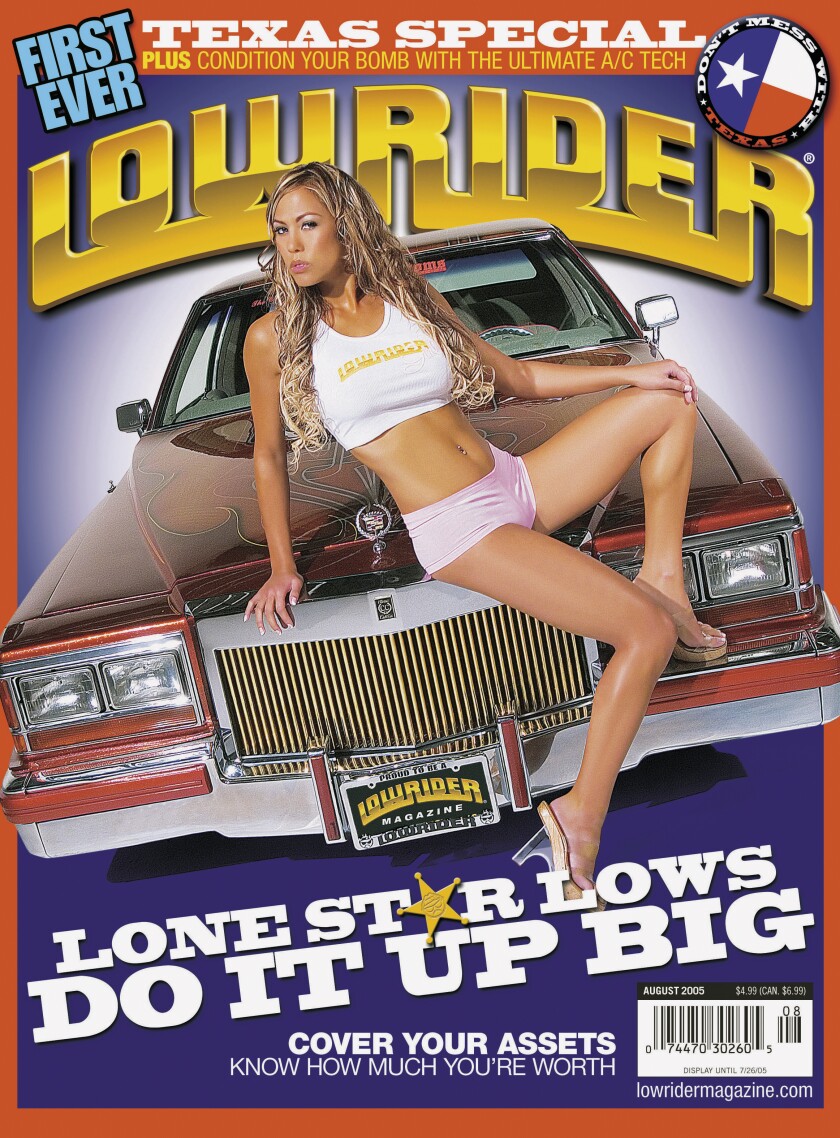

The DIY publication struggled at first. Growth was slow but sales picked up when Lowrider began featuring bikini models on its covers at the end of 1979.

For Navarro, the bikini-clad women were part of the magazine’s appeal.

“There used to be a lot of pretty girls on the magazine,” he said in a phone interview. “The mentality back then was, ‘The better-looking the car, the better-looking girl you’re going to get.’” That combination of gorgeous cars and women, he said, “was beautiful.” (The publication stopped featuring scantily clad women on its covers several years ago.)

Figures such as ex-Olympic boxing champion Paul Gonzales, the legendary stoner duo Cheech and Chong and rappers Ice Cube and Snoop Dogg also graced the magazine’s cover.

In its first generation, Lowrider was more than just a car magazine. It was capturing historical moments within the Chicano community. For one of its regular sections, “Lowriders of the Past,” readers would send in photos of family members posing with their customized vintage cars from back in the 1940s Pachuco era. Another section, “La Raza Report,” featured writeups about political or educational happenings in the community. The magazine also ran a Dear Abby-like advice column, poetry and short stories.

“It was really an art magazine, a community history magazine, all around the love of lowriders,” said Denise Sandoval, a lowrider expert and professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies at Cal State Northridge. It even funded a scholarship program for Latino students.

Though the magazine’s political and social messaging eventually diminished, it continued to celebrate and lift up an otherwise overlooked and underrepresented community.

“At its heart, it’s been a key tool to keeping alive Chicanismo and Chicano identity,” Sandoval said. “I’ve met so many people who are not Chicano, that because they’re part of the lowrider community, they learn about Chicano history through that magazine.” Lowrider also challenged negative, stereotypical perceptions of lowriders as tough thugs and gang members.

In the 1980s, the magazine’s mostly Latino readership started to shift. White, Asian and African American men were immersing themselves in the lowriding world and picking up Lowrider from the stands; the magazine became a multicultural hit.

But its rise in popularity was bittersweet. Others picked up on its burgeoning success and started magazines of their own, eating into Lowrider’s audience. By December 1985, the magazine had gone out of business.

It was revived from bankruptcy in 1988 by its layout designer, Alberto Lopez; his brother, Lonnie (the magazine’s former editor); and co-founder Gonzalez, who moved its headquarters closer to the heart of the lowrider community — Southern California. The shrewd crew noticed the growing popularity of imported mini-trucks and started dedicating much of their content to them.

By the fall of 1988, Lowrider hit 60,000 in monthly newsstand sales; by 2000, it was among the bestselling newsstand automotive periodicals in the country, with an average monthly circulation of about 210,000 copies.

“It was the holy grail for lowriders in the ’80s and ’90s,” said Adan Olivares, 40, a photographer from Santa Ana who was once a devoted reader of the magazine. Every fourth Thursday of the month, a teenage Olivares would trek to his local 7-Eleven to buy the new Lowrider. He’d read each crisp issue back to front before slipping it into a protective plastic cover. Over the years, he amassed hundreds of magazines and filled countless boxes with them.

As the magazine increased its audience, it developed into an empire, adding spinoff titles to its conglomerate (including Lowrider Arte and Lowrider Japan), launched the music label Thump Records, and established a merchandising branch and an events division that sponsored widely popular car shows across the country.

Lowrider Publishing Group was bought in 1997 by McMullen Argus Publishing, which in turn was acquired by Primedia in 1999. In 2007, Lowrider was acquired by Source Interlink Media, known now as TEN Publishing.

While the print cessation of Lowrider marks the end of an era, it represented and solidified what Sandoval called “the codes of the Boulevard: ... Pride, respect, corazón [heart] family, brotherhood.”

In the words of prominent L.A. street photographer Estevan Oriol, who has captured the lowrider world since the early 1990s, “This loss will not affect the community.” With the help of social media and the countless car clubs in existence, aficionados like him together will sustain the cultural legacy Lowrider leaves in its wake.