As the fires raging across California draw national attention, a new documentary explores a time when fires raged across a major metropolitan area — and no one seemed to care.

On Monday, Nov. 4, PBS Independent Lens will premiere “Decade of Fire,” a look at why the Bronx burned in the 1970s, and how some community members chose to stay and rebuild their neighborhoods.

For co-director Vivian Vázquez Irizarry, the film was a chance to understand the forces that shaped her childhood and adolescence.

“Growing up in the South Bronx, I often heard that we were responsible for the neighborhood declining and burning,” she said. “But we did not burn the South Bronx. In fact, we were the ones who saved it.”

Vázquez Irizarry has good memories of growing up in New York City, but there were bad times, too. “There was always a fire. Everyone from that time, we remember the smell of smoke, how the fire trucks didn’t come.”

As a kid, she sometimes slept with her shoes on, ready to flee at a moment’s notice; some families kept their shoes lined up by the front door at night.

Vázquez Irizarry and her partners made “Decade of Fire” to set the record straight about the history of the community she still calls home.

When Vázquez Irizarry’s grandfather arrived from Puerto Rico in the late 1940s, the South Bronx was an integrated community with Irish, Jewish and African American residents. The South Bronx was then a desirable place to live, a step up from the tenements in Manhattan.

In the 1960s, urban renewal projects in Manhattan targeted areas where many African Americans and Puerto Ricans lived, displacing tens of thousands of people who moved to the already crowded South Bronx. As more people of color arrived, whites began moving to the suburbs. As the filmmakers point out, this option was not available to African Americans and Puerto Ricans, who faced discrimination in obtaining home loans or mortgages in many suburban communities.

Meanwhile, under a practice known as “redlining,” any neighborhood with a significant African American or Puerto Rican population was seen by insurers and mortgage lenders as a bad bet. Residents could not get insurance or mortgages and landlords had no incentive to invest in their properties. And as New York City entered a financial crisis in the 1970s, the city made the decision to close firehouses across the Bronx.

“It is hard to accept now, how the city and the state basically ignored the South Bronx,” said Evelyn Gonzalez, a history professor at William Paterson University and the author of "The Bronx," a history of the borough. “It was not just white flight. It was that this area was written off by the people in charge.”

In the 1970s, nearly 80 percent of the housing stock in the South Bronx was lost to fires. Property owners burned their buildings for insurance payouts, or abandoned them altogether. Roughly a quarter of a million people lost their homes. In one scene from “Decade of Fire,” Vázquez visits the Fire Department archives and learns that half of the fires in the South Bronx were never even recorded.

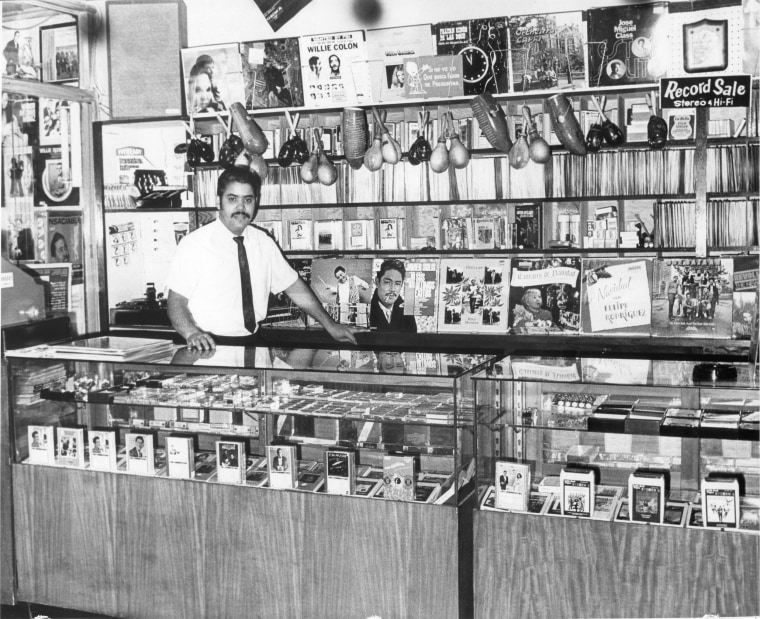

Mike Amadeo, who has owned a music store in the South Bronx for nearly fifty years, remembers the blight of the 1970s. “There were periods when we had no water, no heat. My phone was hooked up, somehow, directly to the telephone pole outside,” he recalled. “It was really crazy; everything was being burned down.”

“I went through hell here,” Amadeo reflected. He stayed, he said, because he loved his customers and the community.

America got its first glimpse of what was happening in the South Bronx during the 1977 World Series, when a live broadcast from Yankee Stadium panned to a nearby blaze. Overnight the South Bronx became a symbol of urban decay, a negative image reinforced by films like “Fort Apache, The Bronx.”

"Blaming the victim"

Vázquez Irizarry saw the effect that such stereotyping had on her community. There is a false narrative, she explained, that when people are poor or live in a bad neighborhood, they don’t know how to take care of themselves or their homes. The truth, she asserts, has more to do with flawed government policies and civic neglect.

“Blaming people for their own oppression is like blaming the victim. It is a convenient way to ignore a community," she said.

The 1970s was probably the low point for the South Bronx, said Juan González, professor of communications and public policy at Rutgers University. “It was like a wasteland back then,” he recalled. Then living in the South Bronx, González was a member of the Young Lords Party, an activist group that tried to help residents preserve city services. The area’s elected officials, he said, were mostly corrupt and disinterested in helping their constituents. At times, street gangs functioned as a kind of police force, since law enforcement was often absent.

It was ultimately grassroots groups that helped bring the Bronx back to life. Some local residents reclaimed empty buildings on their own, remaking them into viable housing for their communities. Nonprofit organizations sprang up, spurring community involvement and demanding services from the city. In 1982, after the city assigned an arson investigation team to the Bronx, the fires that were once so prevalent declined. Another turning point came in 1986, when the city announced a multibillion-dollar plan to build affordable housing.

Since 2010, the Bronx has been the fastest-growing county in New York State, with 56 percent of residents identifying as Hispanic/Latino. Median household income ($37,500 in 2016) is lower than the rest of the city, while the poverty rate (28 percent) is higher.

Now the area faces the threat of gentrification, Gonzalez said. “I never imagined this would happen,” he stated, “but displacement is occurring all over again, for different reasons. Middle-class people want to come to the Bronx, and they are driving out working-class and low-income people.”

Real estate developers have tried to rebrand the South Bronx as “SoBro” and “The Piano District.”

“Decade of Fire” touches upon this broader point: Across the country, neighborhoods like the Bronx in Los Angeles, Chicago, Baltimore and other cities that were once shunned by affluent people are increasingly subject to market forces and development.

Vázquez Irizarry hopes that viewers of “Decade of Fire” will take away not only the struggle of the South Bronx, but also its sense of community and creativity.

“Hip-hop was born here,” she noted. Two of the country’s most renowned Latinas, Jennifer Lopez and Sonia Sotomayor, grew up in working-class Bronx neighborhoods.

To Vázquez Irizarry, the South Bronx is full of unsung heroes. “They are people who stayed and made a difference in their communities. And there are people like that in all our communities.”

“We need to hold on to the pride we have in our neighborhoods,” she added. “To prove that we can tell our own stories, and that we have the courage to survive and thrive.”

By Raul A. Reyes